This month’s Author Takeover comes from the queen of retellings with a twist, Zoë Marriott, discussing her new novel, Barefoot on the Wind, a darkly magical Beauty and the Beast–inspired story set in fairy tale Japan. With Newt scampering around collecting fantastic beasts and Emma taking a feminist slant in her Beauty and The Beast performance, we have some brand new beasts running wild in our imaginations. So Zoë joins us to talk about how she found her inspiration for a different take on the well-known tale, a companion to the critically acclaimed Shadows on the Moon.

This month’s Author Takeover comes from the queen of retellings with a twist, Zoë Marriott, discussing her new novel, Barefoot on the Wind, a darkly magical Beauty and the Beast–inspired story set in fairy tale Japan. With Newt scampering around collecting fantastic beasts and Emma taking a feminist slant in her Beauty and The Beast performance, we have some brand new beasts running wild in our imaginations. So Zoë joins us to talk about how she found her inspiration for a different take on the well-known tale, a companion to the critically acclaimed Shadows on the Moon.

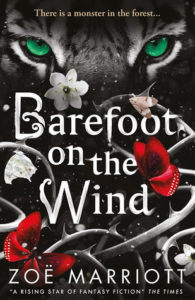

There is a monster in the forest… Everyone in Hana’s remote village on the mountain knows that straying too far into the woods is a death sentence. When Hana’s father goes missing, she is the only one who dares try to save him. Taking up her hunting gear, she goes in search of the beast, determined to kill it – or be killed herself. But the forest contains more secrets, more magic and more darkness than Hana could ever have imagined. And the beast is not at all what she expects…

You can find Zoë on Twitter @ZMarriott

Fantastic Beasts and Where I Found Them

I think I’ve always had a fascination with the idea of beasts. I mean, I’m an animal person, and the relationship between humans and animals obviously interests me because I live with them every day. But a “beast”… they’re different, aren’t they? A beast is something special.

When I was about nine, a helpful librarian (perhaps exasperated by the speed with which I was tearing through the children’s selection, and a bit fearful I was about to sally forth into the adult stacks) handed me a massive Reader’s Digest volume that was as thick as my arm – the Book of Myths and Monsters. It was packed with things that went bump in the night. But the two stories that made the biggest impact on me? Well, the first was Beowolf, which needs no introduction. The second was a folktale from China that featured a malevolent, shapeshifting “Fox Woman.” Her evil was of such magnitude that when she was thwarted, she turned to a pillar of stone, and everything within sight of the stone – plant, animal, and bird – withered away and died. So cool.

I loved these tails – er, I mean, tales – so much that they became a permanent part of my internal imaginative landscape. Anyone who’s read a couple of my books can probably see how they’ve influenced the stories I tell to this day, from the wicked, shapeshifting Zella in The Swan Kingdom to the tortured yet ultimately noble berserker Frost of FrostFire. But why did these beasts, in particular, set my tiny brain on fire to such an extent?

In folklore and fairy tale, the term “beast” is sometimes used to mean “monster.” And “monster” is supposed to mean “bad.” They’re a villain of the piece. At the very least, “beastliness” is a kind of behavior or an aspect of a person that must be defeated and destroyed. But to me, the term “beast” is not interchangeable with “monster.” A beast is something more.

A beast is a creature that partakes of humanity. And because of this, because they seem nearly or partially or even mostly human, it’s as though their beastly nature – which should be alien and repellent to us – instead calls to something, something hidden, within humans in return.

A beast is a creature of the in-between. They dwell in those dark and luminal spaces of the imagination. Whether they’re a shapeshifter, caught between two different forms and two different lives, or a rare and extraordinary kind of animal who can communicate with humans in a way that leaves the humans altered, or even a seemingly ordinary human with a profoundly monstrous aspect, they always remain impossible to safely categorize as one thing or another.

With all this, I suppose it’s no surprise that at a certain point I would feel compelled to tackle Beauty and the Beast. But it wasn’t exactly a straightforward challenge.

Much as we all love it, there’s some icky stuff in Beauty and the Beast. There’s a strange sense that ugly = bad and beautiful = good. The prince has become ugly, but once he permanently acquires beauty again (in the form of a physically attractive young woman) he’s healed of this ugliness, and all is set right. The story is supposed to be about inner beauty and about what makes a man and what it means to be a beast, yet the happy ending is focused on the prince’s physical appearance only. When the tale finishes he has still failed to change his behavior or even apologize to Beauty for the way he’s treated her. I also shied from the way that most descriptions of the supposedly hideous beast emphasize how “dark” he is. Not cool.

When I came to tell my version of the story, I felt my first task was to reverse this idea that ugliness and monstrousness were the same thing – that darkness was bad, and that beautiful things must also, by definition, be good. So for my beast I chose the most beautiful creature I could possibly imagine – the unearthly yet deadly Asian white tiger. My beast isn’t beastly because he’s ugly. He’s beastly because in this form he’s not in control of himself and he is dangerous. But nor is his beauty a bonus. It isn’t in any way attractive. It’s frightening, the way that the lovely, brightly-colored scales of a venomous snake warn off its potential victims. The point was to show that beauty and ugliness are no more clear cut than the idea of what a “beast” truly is.

And having done that, it seemed only right to make my heroine’s beauty entirely separate from her physical appearance, a thing that is utterly about her strength, her kindness, and her resilient soul. The beast can’t, as in the original story, fall in love with her pretty face – because she doesn’t have one. And while I was at it, I flipped some “traditional” gender roles on their head, too. My tortured and self-loathing “beast” would be the one who sang to animals, patched up wounds in a “womanly” fashion, and sewed and made clothes. My heroine was a tough, no-nonsense hunter.

I wanted to really play with these ingrained notions of what a beast is, what beauty and ugliness mean to us. I wanted to dig into those dark, luminal spaces in the imagination – the beastly places – and unearth what hid there. And having written a book in which my beast is beautiful, Beauty is plain, where the humans might act like monsters and the monsters could turn out to be victims seeking understanding and redemption… I’m pretty satisfied with how it turned out. I hope that readers, especially fellow beast fans, will be, too.