In Leora’s society, the most important moments of a person’s life are tattooed upon their skin for everyone to see. People can’t hide their secrets from those around them, and skilled specialists are trained to read the story of a person’s life by the marks on their skin. When a person dies, their skin is tanned and turned into a book of their life – to be either treasured and passed down by their family members, or destroyed if the person is judged to have lived an immoral life. More than anything else, those in Leora’s community fear “blanks” – those who choose to abstain from the practice of tattooing their skin. After the death of Leora’s father, while she awaits judgement on his life, Leora uncovers an alarming family connection to the blank community. The more she learns, the more she comes to question everything she’s ever been told.

I had a little trouble getting into this book at first – I had to set it down and leave it for a few weeks. When I returned to it, I managed to finish it, ultimately concluding that it was okay, if not great. Author Alice Broadway has turned an interesting historical phenomenon – the binding of books in human skin – into an original mythology and culture to go along with the practice. Even though the stories aren’t similar, the pacing and quirks of this book reminded me of The City of Ember by Jeanne DuPrau. Like in The City of Ember, young people are placed in careers early on, and seeing the infrastructure of what jobs Leora and her friends are apprenticed in was one of the book’s most interesting parts.

The part of the book that didn’t quite work for me was that Ink was yet another book that aims to tackle issues of race and politics without actually engaging in them: Leora’s people are prejudiced against blanks because they fear and misunderstand them; the newly elected Mayor Longsight is a zealot determined to crack down on blanks and bring back the old ways; and [SPOILER ALERT] the villainized mythological figure of the White Witch turns out to be heroic after all (uncomfortably resonating with the white savior trope). It seems like Ink wants to be a progressive metaphor for our times, but it falls far short in several places. The end of the book strongly suggests that Broadway intends at least one sequel to this story, but I don’t think I’ll be picking it up.

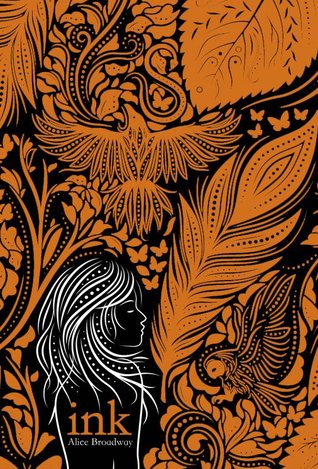

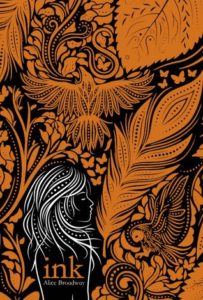

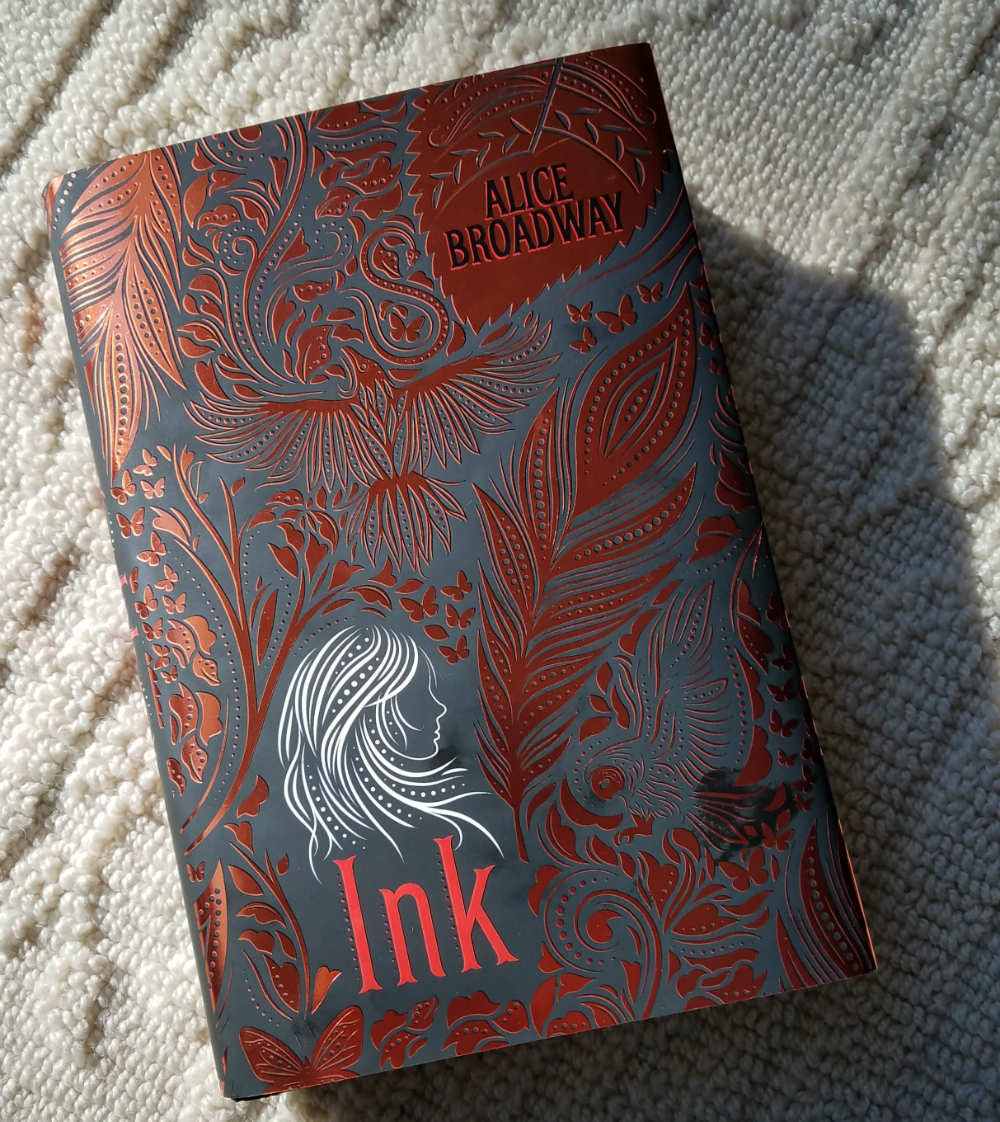

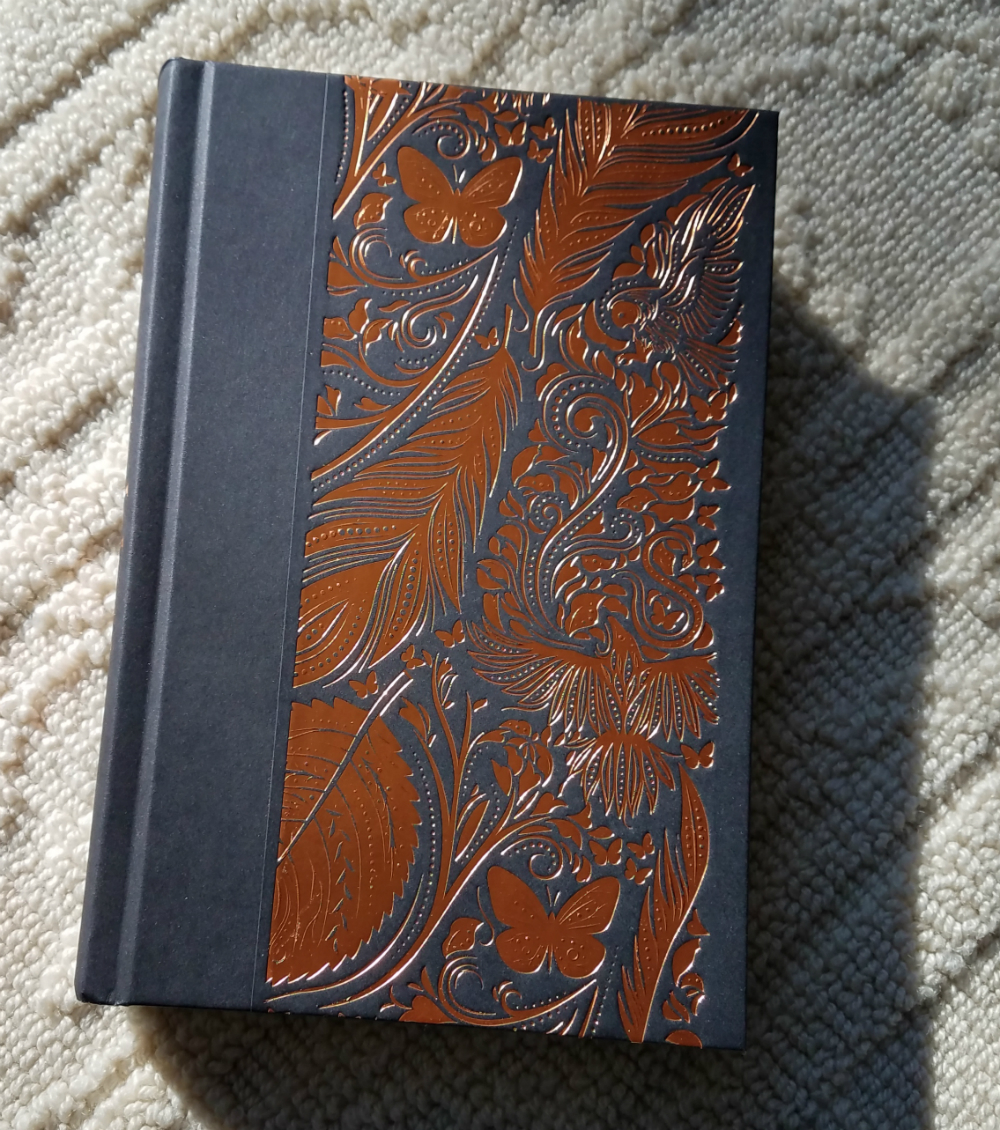

Before I close, I do have to mention that the book itself is unusually beautiful (just look at the pictures below); if only it was as interesting on the inside as it is on the cover.

A copy of this book was provided by the publisher for review.