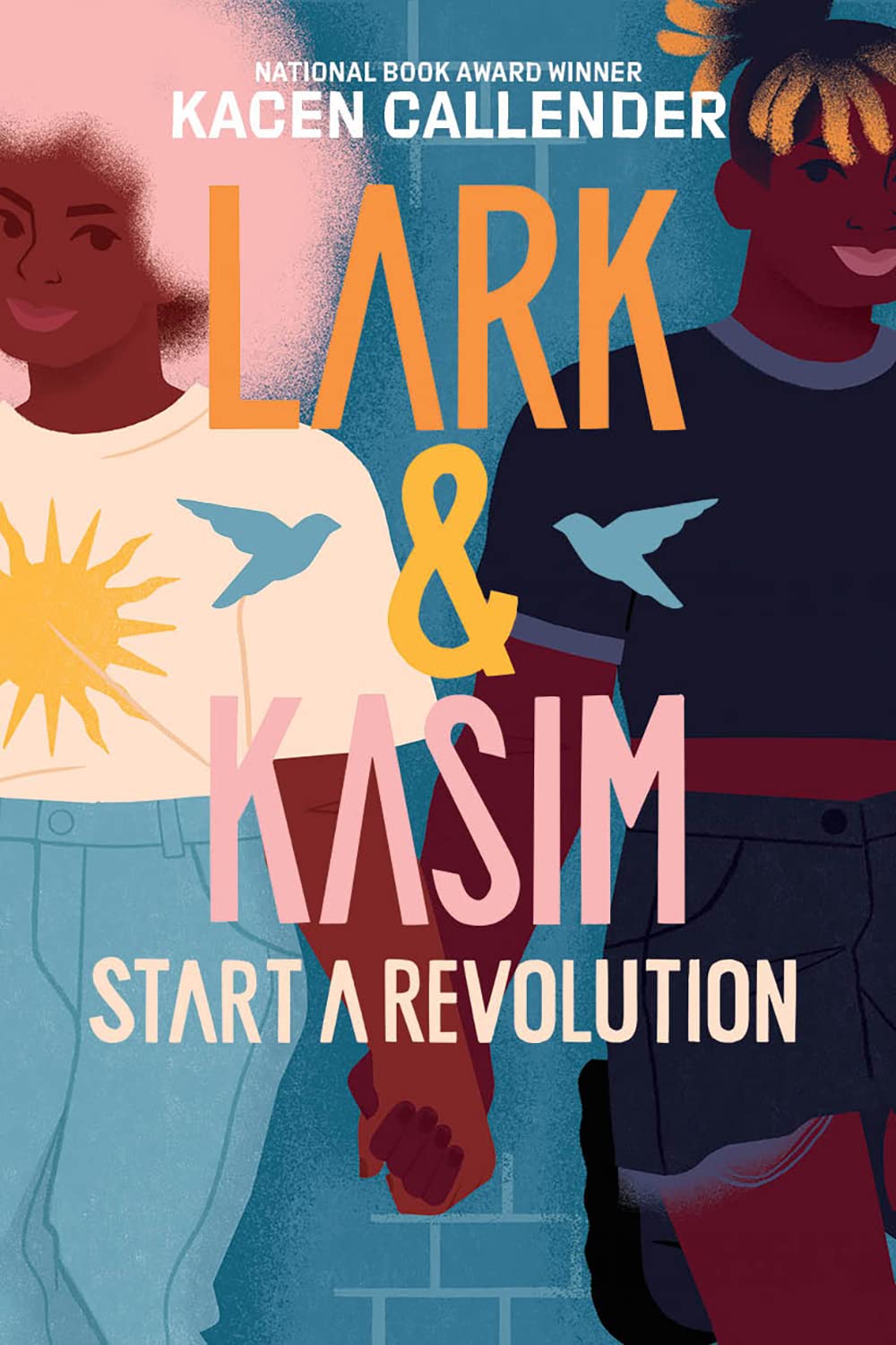

Lark and Kasim used to be best friends, but then something broke between them. Lark (they/them) isn’t really sure what it was, and definitely doesn’t know how to fix it. So for now, they’re focusing instead on their writing career, attempting to build a substantial Twitter following to get agents interested in their debut novel. Things get complicated when Kasim accidentally posts a viral thread about unrequited love from Lark’s account. Lark feels dishonest taking credit for Kasim’s words, but Kasim isn’t interested in claiming them… and their social media followers have increased tenfold overnight. This could be Lark’s chance to attract agents’ interest, but what seemed like a small lie to start with has taken on a life of its own. As Lark navigates their newfound Twitter fame (notoriety?), they’re also working to repair their relationship with Kasim, two experiences that force them to grapple with the same question: How can you love others when you don’t love yourself?

Lark and Kasim used to be best friends, but then something broke between them. Lark (they/them) isn’t really sure what it was, and definitely doesn’t know how to fix it. So for now, they’re focusing instead on their writing career, attempting to build a substantial Twitter following to get agents interested in their debut novel. Things get complicated when Kasim accidentally posts a viral thread about unrequited love from Lark’s account. Lark feels dishonest taking credit for Kasim’s words, but Kasim isn’t interested in claiming them… and their social media followers have increased tenfold overnight. This could be Lark’s chance to attract agents’ interest, but what seemed like a small lie to start with has taken on a life of its own. As Lark navigates their newfound Twitter fame (notoriety?), they’re also working to repair their relationship with Kasim, two experiences that force them to grapple with the same question: How can you love others when you don’t love yourself?

Lark & Kasim Start a Revolution is a rich novel with several different elements at play. Those familiar with Callender’s other novels won’t be surprised to find queer, trans, Black, brown, and neurodivergent teens at the heart of the narrative. Most, if not all, characters inhabit intersectional identities that shape how they move through both the real and virtual worlds. I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler to share that different approaches to moving through those worlds are at the heart of Lark and Kasim’s original rift. Kasim feels that Lark is too concerned with being a people-pleaser, putting way too much energy into making others (especially white, cis, and straight people) feel at ease. Lark, whose genuine lived mantra is to love everyone, no matter what, is hurt by Kasim’s aggressive dismissal of what is, at heart, a survival technique, while also frustrated at his inability to understand that loving everyone doesn’t mean accepting racist, homophobic, or transphobic beliefs or actions. Needless to say, this is not a disagreement that can be easily resolved; it must be worked through, together. Much of the novel is concerned with this work, which I think will resonate with readers who have felt conflicting impulses about the “best” way to live in, survive, and resist a culture foundationally built on white supremacy.

Readers might be divided about the story’s attention to Lark’s ambition to be a published novelist. I think their goal is one likely shared by many potential readers, who will appreciate Callender’s insight into the process, from Lark’s struggle to sell themselves as a social media influencer to the wildly inappropriate responses they receive from some of the agents they query. Their efforts to get their story acknowledged by publishing professionals are central to their struggle toward self-love. At the beginning of the novel, the belief that becoming a published author will validate their existence, making them worthy of love and recognition, shapes too much of how Lark sees themself as a writer; part of Lark’s work in the novel is re-conceiving of their work as something both by and for themselves. But some readers have a hard time enjoying novels with novelists as central characters – something Callender points out in a couple of clever tongue-in-cheek moments. If that’s you, then be warned: A young novelist awaits you within the pages of this book!

This is also one of the few YA books I’ve read that thoughtfully explores polyamory as a viable relationship model for young adults. The characters struggle with communication, balance, and all the other complexities that arise when more than two hearts (and bodies) are involved in a romance, but the possibility is depicted as something that can be the right choice for some people. (And frankly, most monogamous adults could learn something about honest and respectful communication from the teens in this novel.)

Finally, I want to talk about place. I’ve always admired Callender’s skill at evoking place in their novels, and Lark & Kasim is no different – except that the “place” evoked is less West Philly, the neighborhood where the story is set, and more Twitter, the virtual space that propels so much of the action. Callender is spot-on in evoking the feeling of being on Twitter, and (depending on how you feel about Twitter) it’s not a good one. The novel explicitly deconstructs the juxtaposition of social media’s exciting potential to connect people alongside its ever-present toxicity – something it does so accurately that any reader who has ever felt harmed in those online spaces may find it triggering. I tend to avoid social media for that reason, and so I found some parts of the novel difficult to read. But I don’t fault the narrative for my reaction – exposing that side of online life is part of the work Callender is doing with this story.

If any of this intrigues you, I recommend picking up a copy of what feels ultimately like a novel of ideas, one that faces, not un-hopefully, the complexities that arise at the intersection of our real and virtual selves.

A copy of this book was provided by the publisher, Amulet, for review.