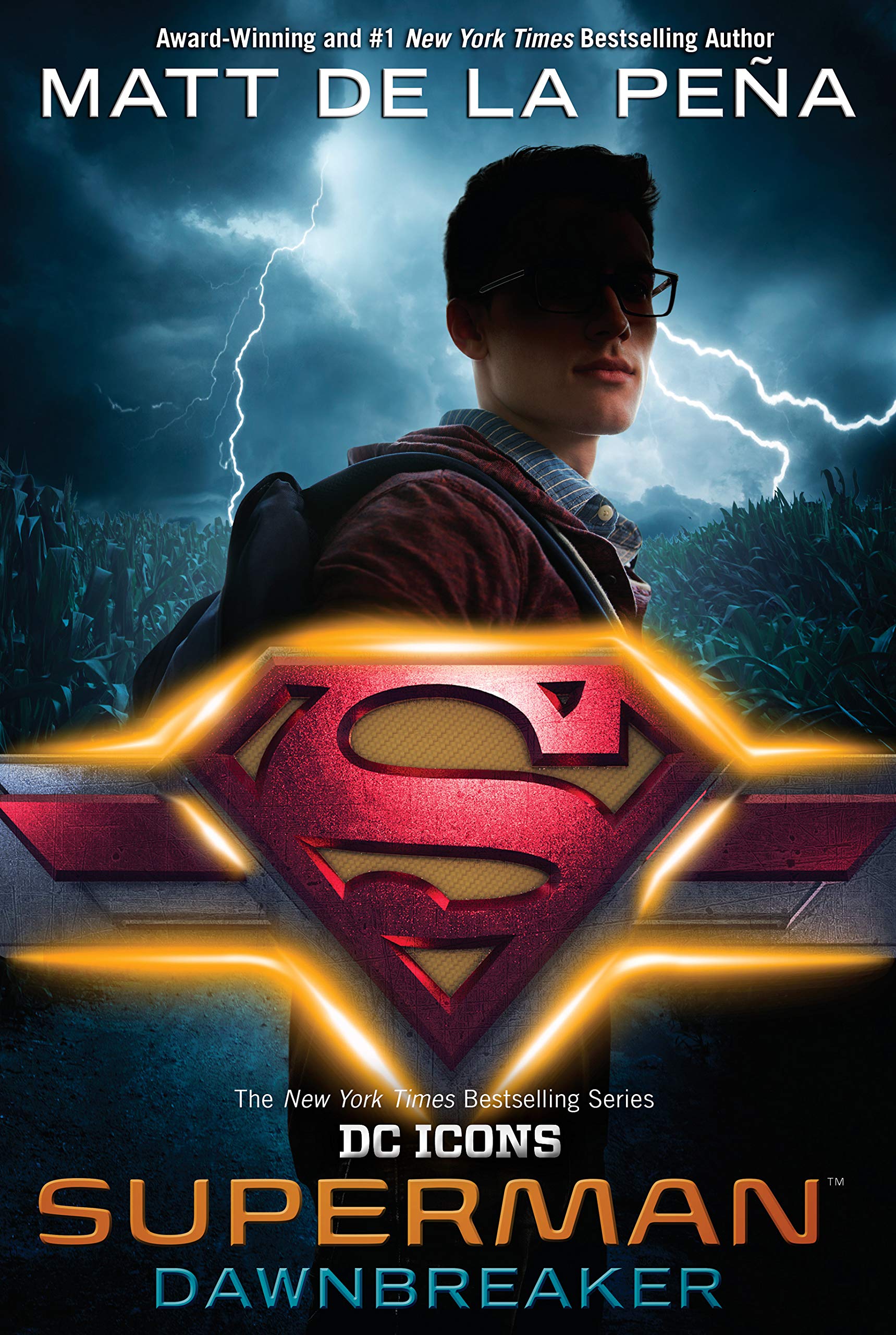

Clark Kent has always known he’s special – after all, it was his unusual strength and speed that made him a football star in his freshman year and his fear of anyone noticing those abilities that made him quit the team after that season, a decision that took most of his friends with it. He’s mostly been a loner since then, except for his best friend and crack student-journalist Lana Lang. But two years later, he’s discovering that he’s more than strong, and more than fast, and he’s beginning to wonder if it has anything to do with whatever his father’s been hiding in their old barn. Clark desperately doesn’t want to be discovered, but when an acquaintance at school – the smart and vivacious Gloria Alvarez, on whom Clark might have a crush – clues him in to the fact that men from Smallville’s immigrant population are going missing, he knows he has to step in.

Clark Kent has always known he’s special – after all, it was his unusual strength and speed that made him a football star in his freshman year and his fear of anyone noticing those abilities that made him quit the team after that season, a decision that took most of his friends with it. He’s mostly been a loner since then, except for his best friend and crack student-journalist Lana Lang. But two years later, he’s discovering that he’s more than strong, and more than fast, and he’s beginning to wonder if it has anything to do with whatever his father’s been hiding in their old barn. Clark desperately doesn’t want to be discovered, but when an acquaintance at school – the smart and vivacious Gloria Alvarez, on whom Clark might have a crush – clues him in to the fact that men from Smallville’s immigrant population are going missing, he knows he has to step in.

Author Matt de la Peña has a hard road to retread for his novelization of Clark Kent’s teenage years. Unlike some other installments of the DC Icons where the central hero’s background remains a bit of a mystery – like Wonder Woman or Catwoman – Superman’s youth has been pretty well covered across a wide variety of media, from the long-running Smallville television show to Gwenda Bond’s excellent trilogy focusing on a young Lois Lane (and that’s not counting Clark’s canonical teenage-hood from the comics). That doesn’t leave de la Peña that much room to navigate, especially when this problem is combined with the old complaint that Superman is “boring,” thanks to his general lack of angst.

What that means for Superman: Dawnbreaker is that even the things de la Peña does really well can seem as if they’re something we’ve heard before; I imagine this feeling is probably compounded for Superman super-fans, ostensibly a major target audience for this book. What Dawnbreaker manages to do, then, is quietly revolutionary. Not only does the main conflict of the novel center on the exploitation of a community of immigrants, but a major part of Clark’s character development involves coming to terms with the fact that his beloved hometown is also a haven for white supremacists, an issue dramatized via an upcoming vote on a racist stop and frisk law.

De la Peña brings one of America’s most iconic heroes into the 21st century by explicitly bringing anti-racism under the generic umbrella of justice that Superman has always stood for. Unfortunately, we are not currently living in an America where that is a non-controversial thing to do; the fact that de la Peña seamlessly makes it seem like a part of the Superman story we think we already know is nothing less than remarkable.

A copy of this book was provided by the publisher, Random House, for review.