[button color=”black” size=”big” link=”http://affiliates.abebooks.com/c/99844/77798/2029?u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.abebooks.com%2Fservlet%2FSearchResults%3Fisbn%3D9781499220155″ target=”blank” ]Purchase here[/button]

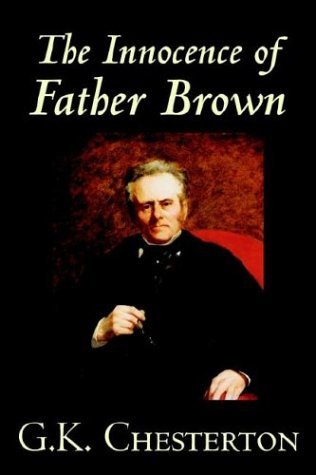

The Innocence of Father Brown

by G.K. Chesterton

When I was a kid, some of my favorite books were mysteries. I read most of Agatha Christie’s books between seventh and ninth grade – as many of them as I could find, at any rate. Some of her books were a little dull, but I loved all the macabre puzzles, sinister clues, and surprise revelations – to say nothing of the unconventional sleuths. Instead of police inspectors and professional snoops, ordinary people solved most of Christie’s mysteries. Extraordinary, ordinary people, to be sure: the keenly observant Miss Marple, the dapper Belgian rationalist Poirot, a nosy housewife named Tuppence, and others of the sort. Through these characters, Agatha Christie was able to do more than pose mysteries and dramatically reveal their solution. She also used them to comment on politics, world events during her long writing career, scientific and technological progress, the social problems of the leisure class, marriage, and aging.

Gilbert Keith Chesterton’s Father Brown mysteries may appeal to a similar taste. Written in the early decades of the 20th century, they celebrate the mystery-solving genius of a little, round-faced, mild-mannered Catholic priest. Chesterton writes with all of Christie’s Englishness, plus a leaner style and a sharper wit. Meanwhile, his main character slides unobtrusively into each mystery, making little impression on anyone until he solves the crime – constantly underestimated, constantly surprising, constantly putting together pieces no one else would have spotted, and constantly making use of his brutally realistic view of human nature, learned by experience as a father confessor.

In the twelve mysteries in this book, Father Brown is nearly always accompanied by his friend Flambeau – a criminal genius turned private detective, whose different worldview often pricks an enlightening contrast to that of the little priest. He solves several crimes before they happen, and prevents them from happening. He saves the innocent from being framed. He discovers the guilt of a martyred hero. And he invariably finds time to make a theological observation – often, mind you, disparaging of Protestantism and other religions.

Each tale is a compelling little who-done-it, breezy and quick and fun to read, with a biting climax and a swift denouement. And each one is also, in its small way, an effort in Catholic apologetics. I sometimes agreed with this last point, sometimes not, but I was intrigued by the connection between a Christian minister’s unvarnished insight into man’s nature and the ability to penetrate the deepest, densest tangle of clues.

I found this book online, thanks to a comment by a reader which included the link. It’s the first time I’ve ever reviewed a book without having held it in my hands. I actually read the whole thing online, using a click of the mouse to turn from one page to the next. It is probably an experiment I won’t repeat very often, since there’s still nothing better than stretching out in bed with a good book. But if I ever have trouble finding even a used copy of something special, I may look for it on Project Gutenberg.