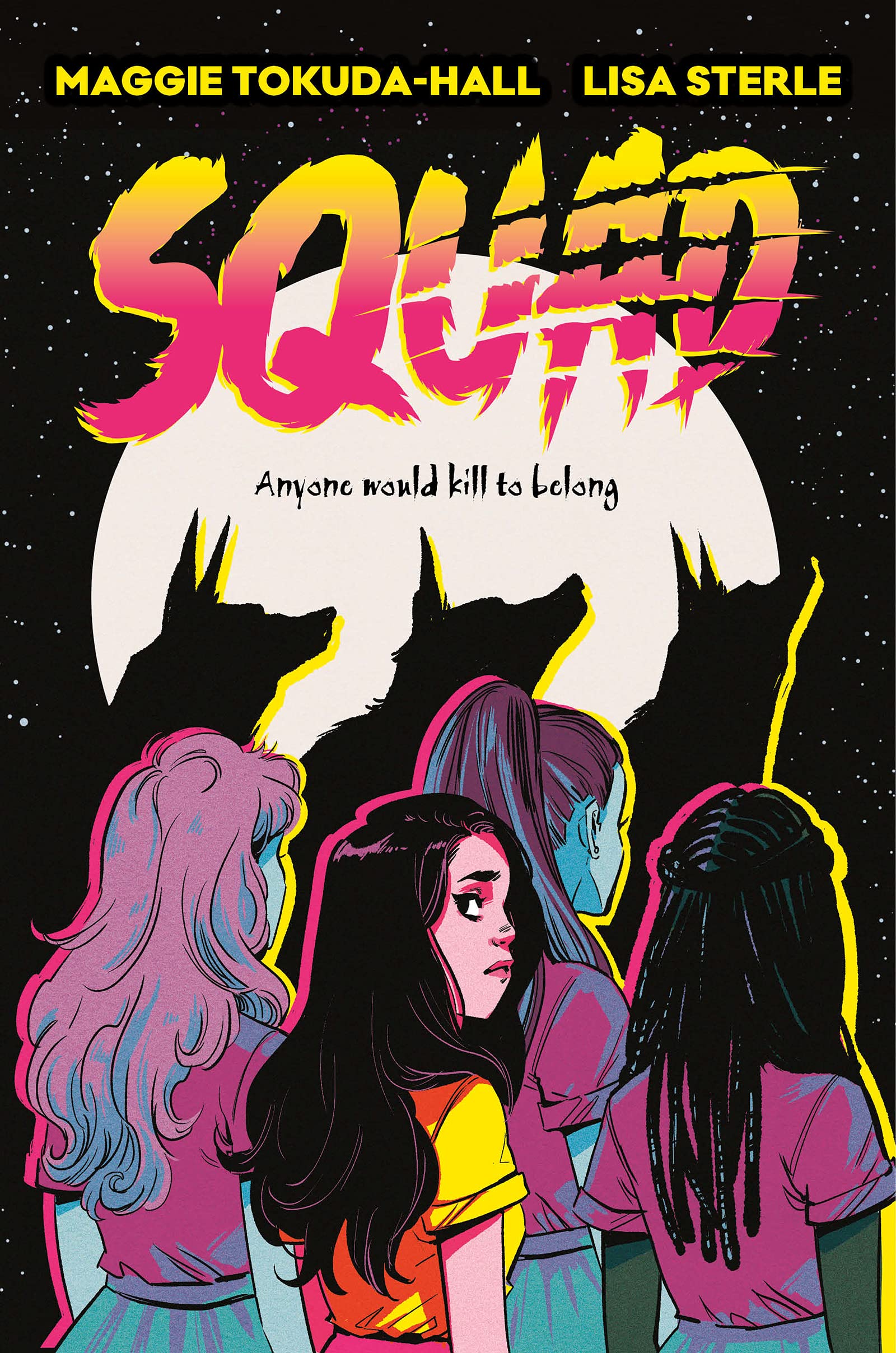

Becca’s never been “popular,” so it comes as a surprise when her new school’s most exclusive clique offers her a spot. Marley, Amanda, and Arianna are untouchable, and Becca already can’t believe they want to include her – it’s almost as unbelievable as the secret they share: They’re werewolves. Once a month the three most popular girls in school become ravenous beasts, preying on creeps who don’t understand that “no” means “no.” But because they need to keep their murders a secret, boys at their own school – including Arianna’s ultra-slimy boyfriend, Thatcher – get a free pass.

Becca’s never been “popular,” so it comes as a surprise when her new school’s most exclusive clique offers her a spot. Marley, Amanda, and Arianna are untouchable, and Becca already can’t believe they want to include her – it’s almost as unbelievable as the secret they share: They’re werewolves. Once a month the three most popular girls in school become ravenous beasts, preying on creeps who don’t understand that “no” means “no.” But because they need to keep their murders a secret, boys at their own school – including Arianna’s ultra-slimy boyfriend, Thatcher – get a free pass.

Despite the whole murdering people part of it, Becca has to admit that being a werewolf feels great. She’s fast, strong, and powerful. It feels good to be able to fight back, and it feels great to know that, as part of a pack, you’re never alone. But things begin to get more complicated as the year goes on. In the frenzy of hunger that overpowers the girls once a month, some boys get killed (and eaten) who don’t really deserve it, and tensions run high among the friends as they clash over right and wrong. When a boy at their own school dies, it starts to seem like everything might unravel once and for all.

I was really excited to read this graphic novel, and I’m interested to see how it will be adapted for television. But I have to admit that I didn’t like it as much as I thought I would, with most of my reservations coming from the graphic novel’s version of feminism, which felt shallow for a narrative that is ostensibly about young women’s stifled rage and hunger.

For example, a major area I felt was lacking was in the graphic novel’s depiction of beauty standards and disordered eating. Becca isn’t admitted to the group because of her personality; she’s admitted because she’s “so pretty.” All four of them are, which would be fine – if being “so pretty” weren’t the standard by which it was determined whether or not you get access to power. The power to protect yourself, to feel strong, and to fight back are only bestowed on young women who achieve a certain standard of beauty.

Much of this standard seems based on thinness. When the girls go shopping together, they are surprised to learn that Becca is a size four (mon dieu!) instead of a size zero or two; Amanda observes that Becca is “gonna have to keep that SMALL FOUR under control if she wants to share clothes with us.” They also don’t eat lunch – to be fair, they are werewolves, so they don’t need to. But Squad leaves you with the definite impression that they wouldn’t eat lunch even if this weren’t the case.

Several scenes of Becca and her mother also suggest that Becca’s mom has internalized a lot of shame around eating. After the pair have salads for dinner, Becca’s mom proposes that they “be bad” and have macaroni and cheese, too, a suggestion Becca interprets as her mother wanting the mac and cheese but not being willing to eat it “unless someone gives [her] permission” – something Becca refuses to do. Another time, as the two leave a workout class, Becca complains that her mom only pretends to enjoy exercising because she “feels fat” and that “this pain is [her] punishment.”

I think these moments are meant to provide a contrast to the wild appetites the girls indulge in their werewolf forms, needing no permission and feeling no shame as they eat (people) to their hearts’ content. But it bothers me that the novel suggests that the only way to do this is by hurting someone else, and that Becca’s mom’s struggles are only ever treated with annoyance rather than sympathy. And the big ringer, of course, is that through the ups and downs of drama, the four girls’ own thinness remains unimpeachable and effortless, werewolves or no.

It’s almost as if Squad wanted to critique the way anti-fatness makes women police their own and others’ bodies, but instead, it just depicted it. Everything that’s wrong with the scenes I mentioned above is never directly addressed. Yes, isn’t it awful the way we’re taught to hate our own bodies? Wouldn’t it be more convenient if we didn’t? Wouldn’t it be most convenient of all if we were just so pretty and thin that we never had to worry about it at all? Squad offers a metaphor that never quite adds up, a collapsing house of cards that I think harms rather than empowers.

Some other small things about the book: It also bothered me that the temporal transitions were often confusing and that the whole murdering of innocent people barely seemed to register on the girls’ consciences – but not as much as its anti-fatness did. Squad has a great concept and has a lot of potential for exploring questions around women’s anger, sexual assault, female friendship, and beauty standards. It’s certainly possible to read the book and appreciate its campy horror if you don’t ask it to go deeper than surface level on any of the above. I will say that I think the creators’ intentions were good – but the execution is clumsy.

A copy of this book was provided by the publisher, HarperCollins, for review.