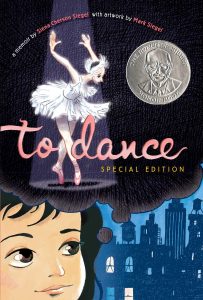

Originally released in 2006, Siena Cherson Siegal’s graphic memoir To Dance has just been re-released in an expanded edition, which means it’s the perfect opportunity to either revisit this slim volume or discover it for the first time. In its pages, Siegal chronicles her early infatuation with dance as a child in Puerto Rico and her adolescence as a student at the School of American Ballet. Her story is rendered visually with graceful and evocative illustrations by Mark Siegal, allowing the reader to become hypnotized by the beauty of ballet along with the young Siena.

Originally released in 2006, Siena Cherson Siegal’s graphic memoir To Dance has just been re-released in an expanded edition, which means it’s the perfect opportunity to either revisit this slim volume or discover it for the first time. In its pages, Siegal chronicles her early infatuation with dance as a child in Puerto Rico and her adolescence as a student at the School of American Ballet. Her story is rendered visually with graceful and evocative illustrations by Mark Siegal, allowing the reader to become hypnotized by the beauty of ballet along with the young Siena.

I took dance lessons when I was four or five years old, but, much to my mother’s chagrin, I was never really a dancer. I didn’t understand whatever the appeal was for some students, and when my mom stopped making me go to my lessons, I quit without a second thought. (Not that I was prone to giving most things a second thought at that age.)

I bring up this anecdote because I think one of this book’s most remarkable achievements is bringing that appeal alive in its pages. Through Siena’s eyes, I can see what ballet never was for me personally: a community, an art, an obsession, and a passion. Her experiences at the School of American Ballet and performing with the New York City Ballet made me want to watch a ballet performance (which I haven’t done since I fell asleep during The Nutcracker on a school field trip). To Dance is a natural fit for young people who are aspiring dancers themselves, but even those without a connection to dance should consider giving this book a chance.

I also appreciated that this book can speak to young artists at so many stages of their work. The story ends with Siena giving up dance at the age of 18, an ending that in other circumstances might have fallen flat after the exuberance with which she tells about her life as a dancer and the hard work she put into being a ballerina (especially since the more controversial aspects of being a dancer – including painful injuries, the specter of eating disorders, and the general scrutiny on young girls’ bodies – are only referenced in passing). But Siena’s choice is presented not as a failure but simply a change, with the acknowledgment that the one thing that will stay with her forever is her love for dance itself. Whether young dancers are just starting out or considering how dance will fit into their futures, they will find an ally in Siena.

My one recommendation for parents with children seriously pursuing dance would be to speak with them about some of the issues that are understated in the graphic memoir itself. For instance, Siena doesn’t write anything about being encouraged to eat less or the prevalence of eating disorders in young dancers, but there is a time-lapse panel that shows an aging Siena with less and less food on her plate as she grows older. I don’t think it’s a failing of the book that such topics are treated in this way – fundamentally, this book is about joy, despite whatever else goes on in the dance world – but using this book to spark such conversations could help young dancers feel less alone if they face similar issues.

I also really enjoyed seeing the real-life photographs and mementos from Siena’s dance career in the back of the book. It saved me from Googling many of the fascinating things that sparked my interest as I read the story!

A copy of this book was provided by the publisher, Simon & Schuster, for review.