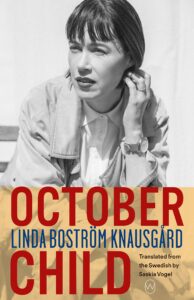

Linda Boström Knausgård has a famous name, a fact that’s not entirely of her own making, despite the fact that she is an accomplished novelist and poet. She’s also the ex-wife of writer Karl Ove Knausgård, whose series of autobiographical novels, My Struggle, became an international literary sensation soon after their publication.

Linda Boström Knausgård has a famous name, a fact that’s not entirely of her own making, despite the fact that she is an accomplished novelist and poet. She’s also the ex-wife of writer Karl Ove Knausgård, whose series of autobiographical novels, My Struggle, became an international literary sensation soon after their publication.

I mention this at the beginning of this review not to define Linda’s accomplishments in light of her husband’s but because their marriage features, inevitably, as a subject in the books that made his reputation. I’ll admit that I haven’t read them myself, and so what I’m about to say may not be entirely fair – but it seems like it would be difficult to live as a character in someone else’s narrative, even with the questionable caveat that My Struggle is, on some level, supposed to be fictional. When the characters share the names and much of the history of real, living people, it’s easy to see how one might feel that their very self was being overwritten by another hand.

Now, there’s probably a fair amount of projection in the above interpretation (it is how I would feel in Linda’s position), but I do think considering this context helps us make sense of what’s going on in her own autobiographical novel, October Child. In the novel, the narrator recounts the experience of being periodically interned in a psychiatric ward where electroconvulsive therapy was a regular part of her treatment. A common side effect of this treatment? Memory loss. As she works to overcome her illness, the narrator also feels that she is losing herself, one memory at a time. Who are you when you’ve lost the narrative of your own life?

The narrator has been assured that, for most patients, the memory loss is temporary, and she begins writing down recollections as a way of recalling herself to herself, a process that is as much about the act of writing as it is about the memories she records. We glimpse the narrator as a child, a teenager, a mother: disconnected snapshots of a life interrupted by mental illness. We see, too, the breakdown of her marriage to a well-known writer, as well as flashes of the brusque and alienating experience of being a patient whose schedule, activities, and treatment are all dictated by other people. The indictment of mental health care is scathing.

Ultimately, October Child is about control – lost, regained, and otherwise. It’s a theme that’s worked into the novel’s very DNA, integral to its sparse and powerful prose; the narrator may feel out of control, but the novel never does. Many of Boström Knausgård’s observations and reflections, as voiced through her novel’s central character, are poignant in their clarity, and what may at first seem like fodder for melodrama (divorce, suicide, mental illness, the power of memory) is anything but saccharine. While the atmosphere of October Child may feel more suited to the chilly air that the title evokes than to the sweltering heat of summer, thoughtful readers will find much to relish here.

A copy of this book was provided by the publisher, World Editions, for review.